Hundred Years War

Part II - Northeast Conflict Zones 1733-1866

Introduction

The tribes and the Europeans of the Northwest Atlantic formed a sprawling trade network linked by innumerable lakes, rivers and water bodies and brokered through swirling political alliances.

Native Americans fought over access and politicked for friendly relations to British or French traders. Ultimately this strategy would lead to successive waves of undoing - as the British finally defeated the French and drove the French from the continent, the former French allied natives were suddenly dispossessed relative to their British allied rivals. Later, the same process would repeat to the British allies after the American revolution. And again the Civil War between the states would dispossess the southern tribes, like the Cherokee, who aligned with the losing Confederacy. However, those big historical movements took place within decades or centuries to unfold. In 1733, the French were it north and west of the Hudson Bay.

In part I - we described the general lay of the land and major players as documented by Pierre La Verendrye in 1733 -

Picking up from there - what follows are the critical events of the war between the Sioux, Ojibwa, Cree and Assiniboin that turned Minnesota into a war zone for a century and half.

The Spark

“All of northern Minnesota soon became a ‘no man’s land’, inhabited by mostly marauding war parties. The bands were not large, usually less than 100 in number, but they were devestating.” - Lund. Page 58.

Reports of war parties come to Fort St. James. The Cree are fighting the woodland Sioux to their southwest over access to rich hunting and trapping grounds.

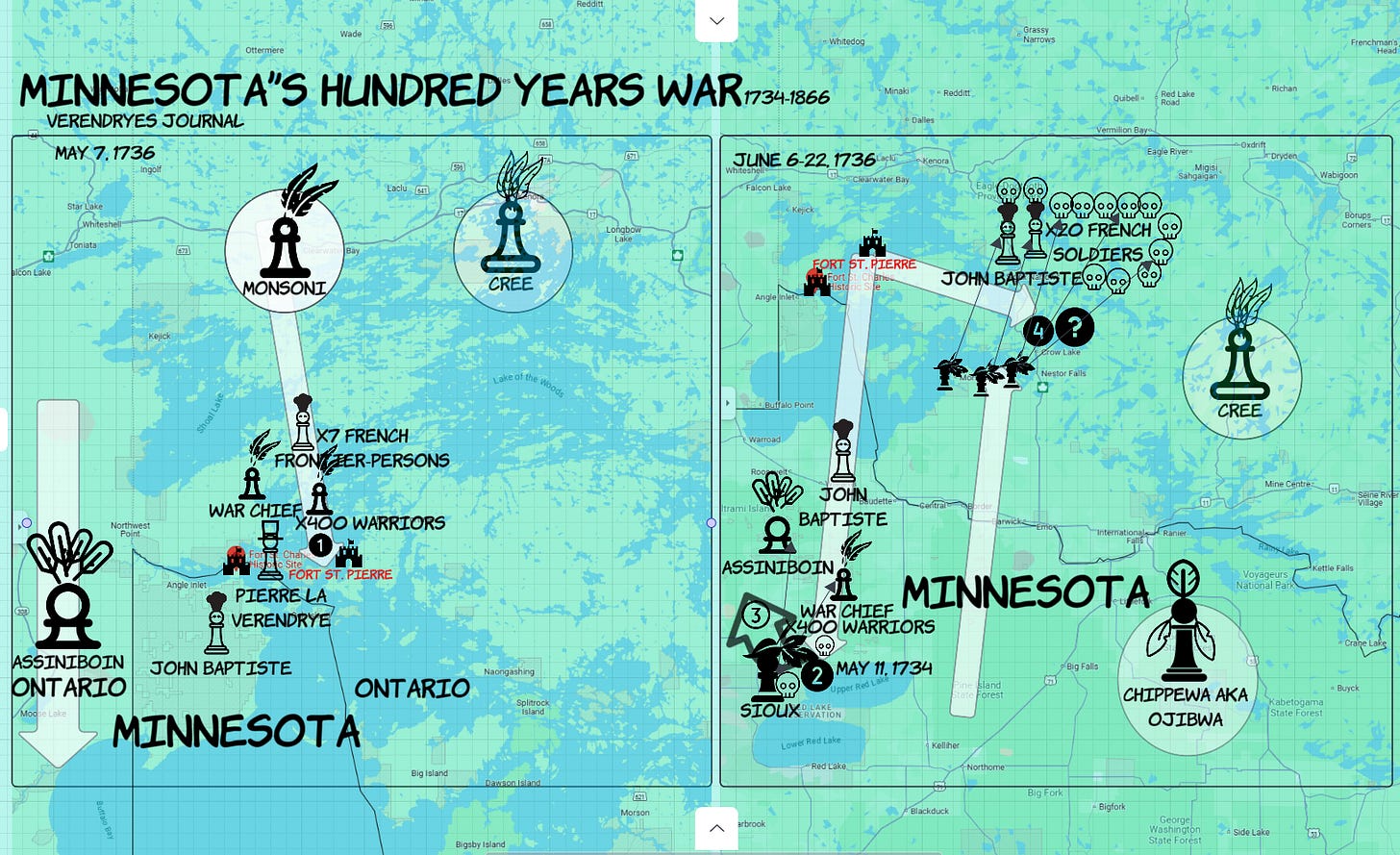

[1] Seven Frenchmen who wintered at Fort St. Pierre (?) arrive with 400 Monsoni warriors on the path at Fort St. Charles, where Verendrye sits as the administrator of French trade in the region.

When Verendrye tries to dissuade the warriors from attacking the Sioux, as the French trade with some of the Dakota Sioux, a canny war chief (unnamed) insists Verendrye’s son, John Baptiste, accompany the warriors so he can make sure they do not attack France’s friends. Baptiste is stoked to go, forcing Verendrye’s hand.

“On the one hand, how was I to entrust my eldest son to barbarians I did not know, whose names I did not know, to go fight against other barbarians whom I did not know and of whose strength I knew nothing. On the other hand, were I to refuse them, there was good reason they would take us French as cowards. As a result, they might shake off the French yoke.” - Pierre Verendrye. 1736. Lund. pg. 42

(Orwell described a similar colonial experience of feeling powerless to exercise power in Shooting an Elephant.)

[2] The warriors, with John Baptiste in tow, meet up with the Assiniboin to attack woodland Sioux settlements near the Red Lakes and [3] the party returns without incident.

[4] June 6th trouble has arrived again - Verendrye dispatches 21 men, including his son John Baptiste, on canoes with goods to give as mollifying gifts. Verendrye receives a letter from his man that the Sioux have captured them. Then the men are found killed on an island by Cree search parties (unknown exact location today.)

The killing of the French and Verendrye’s son inflames Cree and Monsoni warriors. They take to the war path for retribution. War parties come and go through the summer, prevailing upon Verendrye to accompany them on a war path. After resisting time and again, Verendrye finally releases a statement pointing out his duty is to the French interests in trade, not to avenge his son’s death or make war. Verendrye points out John wanted to go to war and seems at peace with the consequences. Despite Velendrye’s attempt to keep the peace, the slaying of the Frenchmen and John Baptiste sparks a long war.

Turning Points

[5] “The Dakota (Sioux) villages at Sandy Lake were the first to fall. The key to controlling the area, located on the watershed between Lake Superior and the Mississippi Lake region at the end of the Savanna portage, the site became the new capital of Ojibwe nation… By 1739, the Dakotas had moved back to the Minnesota River...

No sooner would the Sioux be driven back than they would plan a counterattack. If the Ojibwe moved out of an area, the Dakotas moved back. Old village sites were settled and resettled. - Lund pg. 58

[6] “When the Ojibwa war party left Fond du Lac, it was said that a man standing on a high hill could not see the end or the beginning of the line formed by the warriors walking in single file - as was their custom.” - Lund. Page. 58

[7] The Dakota Sioux lose the war when they split their forces and attack Sandy Lake, Pembina and Rainy Lake. They lose all three battles. Ojibwa Chiefs Bi-Aus-Wa, Noka, Great Marten and White Fisher are credited with leading the victory.

After this loss in 1766 the Sioux were firmly pushed back to the Minnesota river. Though the Sioux were defeated, intertribal fighting continued up until the American Civil War. The last Native American-White battle took place in Minnesota in 1898.

The below are illustrations of some of the many battles (most lost to history) that raged across the state of Minnesota.

Prompts

The Cross Lake Massacre 1800

Henry Schoolcraft Peace Keeping Mission - 1832

Curly Head’s brother Hole-in-the-Day I’s vision - 1820s

Flat Mouth’s Revenge Party - 1832

Northeast frontier trade statistics reproduced from Commerce by a Frozen Sea.

CFS goes on to list many more trade statistics for goods such as brandy, tobacco, bayonets, beads, buttons, combs, egg boxes, handkerchiefs, lace, spoons, sword blades, thimbles and so on. Grouped into Producer, Household, Alcohol & Tobacco, and Luxury goods. In other words, the northeast fur trade was a big part of the economy, but hardly all of it - the native people may have been more similar than different than people of today - ready to fight and die for the good life.

References

Lund, Duane R. The Indian Wars. Cambridge, Minn., Adventure Publications, 1995.

Carlos, Ann M, et al. Commerce by a Frozen Sea : Native Americans and the European Fur Trade. Philadelphia, University Of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.