Introduction

Apache refers to the Athapaskan speaking peoples of the American southwest, in the present-day states of Arizona and New Mexico.

This series will explore the critical battles, wars and movements of Apacheria.

https://crackpot.substack.com/t/apacheria

Context

This is part III of an interrogatory of the major parties to conflict in the Apacheria-Arizona New Mexico territory of the 19the century.

Previously we looked at the Apache and the military. Now we turn to a third party; the settlers.

Citizens

The Walker Party found Prescott, Arizona in April, 1864.

[1] January 1864 - Walker Party member Abe Peeples rallies a party to retaliate for the loss of 27 head of stock to raiders.

[2] King S. Woolsey leads Peeples’ party through Arizona. They pass the Hassayampa River, Aqua Fria. Maricopa warrior Juan Chivaria and some warriors, as well as Cyrus Lennan and a few Pima join the party when they resupply in Pima village.

[3] The party continues through the Salt River and to Fish Canyon where a large party of Apache warriors present themselves.

[4] Woolsey offers a parlay with gifts with Chief Par-a-muck-a and six other chiefs. Tonto Jack, a Yuma working with Woolsey, facilitates the discussion between the Apache and Woolsey.

Woolsey pretends to be friendly. Knowing the Apache cannot understand his words, Woolsey picks out a chief for each man to shoot while shaking hands. Then on Woolsey’s word they surprise attack the Apache - killing the chiefs.

“In a crashing instant five of the six chiefs were slain, the blood of the most important pouring onto the scarlet blanket. The sixth chief, shot twice, raised a lance with a rusting Mexican saber for a blade, and rammed it through the heart of Cyrus Lennan.” - Thrapp pg. 30

[5] After a short battle, the stunned Apache warriors withdraw. It is believed the battle took place in Fish Creek Canyon. The brief fight was a running battle through a wash, which may be the one indicated.

This incident is representative of the extermination policy - and the active role militant American settlers played in violence.

Treacherous acts like James Johnson surprising Juan Jose Compa and other Indians with a howitzer at dinner or ploys to capture Mangas and Cochise with offers to parlay, abound in the Apache war.

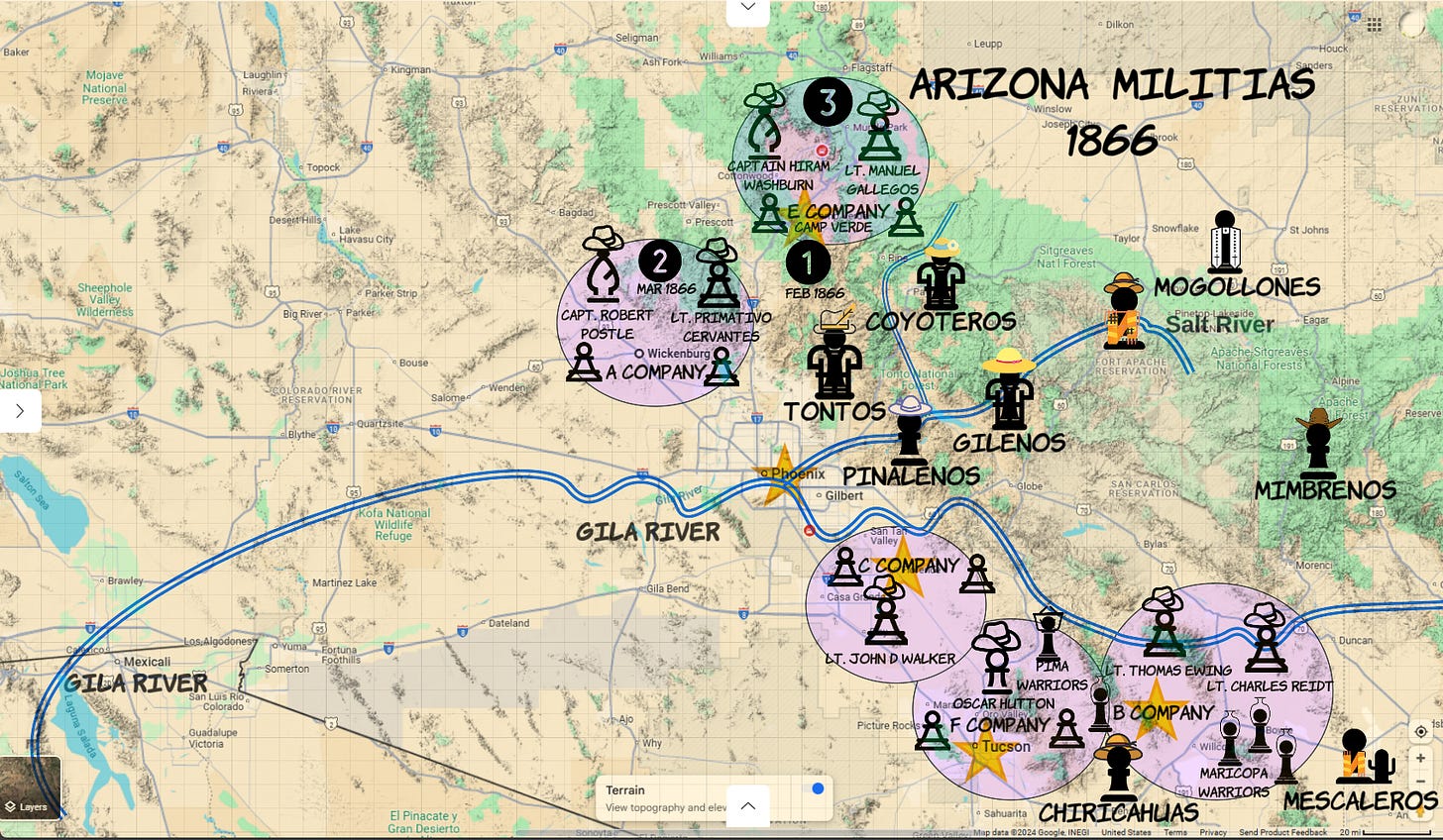

1865-1866 - Arizona created five companies organized to replace the California Volunteers, who depart Arizona territory at the end of the Civil War. These are company A, B, C, E and F company. (Why no D? No mention of a D in the text.) Though brief lived, these organizations were active and outlived by the cycles of destruction they perpetuated in motion.

Pima and Maricopa warriors worked with the militias.

[1] Company E, commanded by Lt. Gallegos, ride into Apache territory attack and kill a number of Apache living in caves.

“One war chief held a secure, elevated position and successfully defied the attackers, but his followers were not so fortunate. All the caves that were accessible were filled with dead and wounded.” - Thrapp pg. 35

[2]

“John Walker and Company C Pimas plus Company B Maricopa attacked the Apache… The Pimas placed the head of the fallen on a flat stone and crushed it with a falling rock.” - Thrapp. ibid.

[3]

“Sergeant Elias and six men of Company E fought 27 Apache while on wagon train escort near Prescott. Elias had a bullet through his hat, and one of his men was captured and recaptured three times, but the Indians quit just as the detail was running out of ammunition, and no one was killed on either side. - Thrapp. ibid”

Thrapp notes the Volunteers disbanded soon. The next idea was a ranger outfit with Tom Hodges as captain.

“Surely, we need rangers, native volunteers, or more regulars to go in pursuit of the red rascals … We are glad our Yavapai Rangers do not trouble themselves with making prisoners of murderous red skins. All in sight are made to bite the dust.” - Prescott Miner newspaper. 1866

Like the militias, the rangers were not for long. Indian fighting was difficult and doing it as volunteer without pay made volunteer or citizen militias difficult to sustain. So the short-lived experiment with militias died and the citizens of Arizona turned again to the U.S. military to fight.

Militia Campaigns

The citizens (especially newspapers) had a love-hate relationship with the U.S. military. On the one hand, the military was too slow and incompetent to stop depredations. On the other hand, many citizens made a living supplying the military - and in truth the citizen actions caused a lot more problems than they solved. With typical American ‘know-it-all everyone-else-is-an-idiot-i’ve-got-the-answer-five-minutes-after-i-walk-into-the-room’ attitude, the idea of taking matters into their own hands kept coming back around like a whirlwind. This is a brief story of an expedition led by Bill Ross to fight Chiricahua Apache in Chihuahua, Mexico.

[1] May 1882 Bill Ross leads 50 frontier persons out of Tuscon, Arizona.

[2] The rangers encounter a group of Indian, mostly women and children, whom they kill.

[3] The ranger encounter a force of Mexican military under Captain Ramirez. Ramirez detains the force - disarming them.

[4] General Reyes and Colonel Garcia arrive in force.

Ultimately Officer Ramirez disarms the Tuscon gang and spares their lives. The gang was disarmed and booted out of Mexico. The resourceful Ross had each man cut it a short pole and lay it across his saddle horn as a bluff so the men would look armed on the 300-mile trek back to the United States and Tuscon. The humiliated men arrived home in Tuscon without further incident.

“We give this act of the citizens of Arizona most hearty and unqualified endorsement. We congratulate them on the fact that permanent peace arrangements have been made with so many, and we regret that the number was not double.” Denver News. 1871

Papago is an antiquated name. Tohono O’odham is modern.

[1] Feb 1871 Lt. Whitman arrives at Camp Grant.

[2] Feb 1871 - Five Apache women unexpectedly arrive at Camp Grant with a flag of truce. After meeting with Lt. Whitman more Apache arrived - including Eskiminzin, an Arivaipa Apache, and 25 of his warriors. Eskiminzin says they are tired of fighting and only want to live in peace on their own land.

Whitman receives the Apache in a growing camp. Whitman dispatches a letter to General Stoneman, commanding officer of the Department of Arizona, to solicit instructions on how to proceed with the peace process. General Stoneman never receives the message due to a clerical error on the postage.

[3-4] Spring 1871 - A series of raids in the area occur at the same time the population of Camp Grant is established. Including the killing of a miner near Tubac, raids in the Santa Cruz and San Pedro Valleys, and an attack on a wagon train west of Camp Grant.

These actions inflame the citizens of Tuscon, who believe the warriors involved in the raids are also sheltering in Lt. Whitman’s camp Grant. The military commanders of Camp Grant claim otherwise on the basis of inspecting the camp for arms and closely monitoring the coming and going of persons, but public opinion was not satisfied with the military self-acquittal.

[5] April 1871 Captain Stanwood arrives to take command of Camp Grant.

[6] Apache raid cattle and horses from Papago in San Xavier.

A group of settlers in Tuscon join the Papago warriors in a 50-mile pursuit of the Apache raiders. They recover the horses and kill one raider. The success of the joint effort leads to

[7] April 30, 1871 - Citizens take matters into their own hands. A Tuscon citizens meeting is held. Juan Elias represents the Mexicans. William S. Oury represents the Anglos. Francisco represents the Papago. They decide to form a war party and attack the camp. The war party contains 48 Mexican fighters, 6 Anglos (the 80 some white men who initially promised to go welched) and 94 Papagoes. The raid is a success. The war party kills scores of the Apache staying at Grant under the promise of protection and peace of the U.S. military.

“I no longer want to live”, Eskiminzin told Lt. Whitman after the Camp Grant Massacre.

“All but 8 of the 144 were women and children, ravished, wounded and clubbed to death, hacked to pieces or brained by rocks. A few tried to clamber up the sides of the wash, but Anglos and Mexicans shot them down. They tumbled back into the hands of the Papagoes to be clubbed to death. Not a member of the attacking party was wounded. It was sheer, unqualified murder. Less fortunate than the dead were the 27 children taken prisoner, sold by the Papagoes into Sonoran slavery.” - Thrapp pg. 90

Related

What was happening outside Apacheria in the 1860s?

The war between the states from 1860-1865 pulled the best officers and soldiers away from the frontiers of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska and other interior states east.

References

Gwynne, S. C. (2010). Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the rise and fall of the Comanches, the most powerful Indian tribe in American history.

Cornelius C. Smith, Jr. Fort HuaChuca The story of a frontier post.

Thrapp, D. L. (1975). The conquest of Apacheria. University of Oklahoma Press.

Worcester, D. E. (1979). The Apaches Eagles of the Southwest. University of Oklahoma Press.

Melody, M. E. (1989). The Apaches. Chelsea House Publishers.